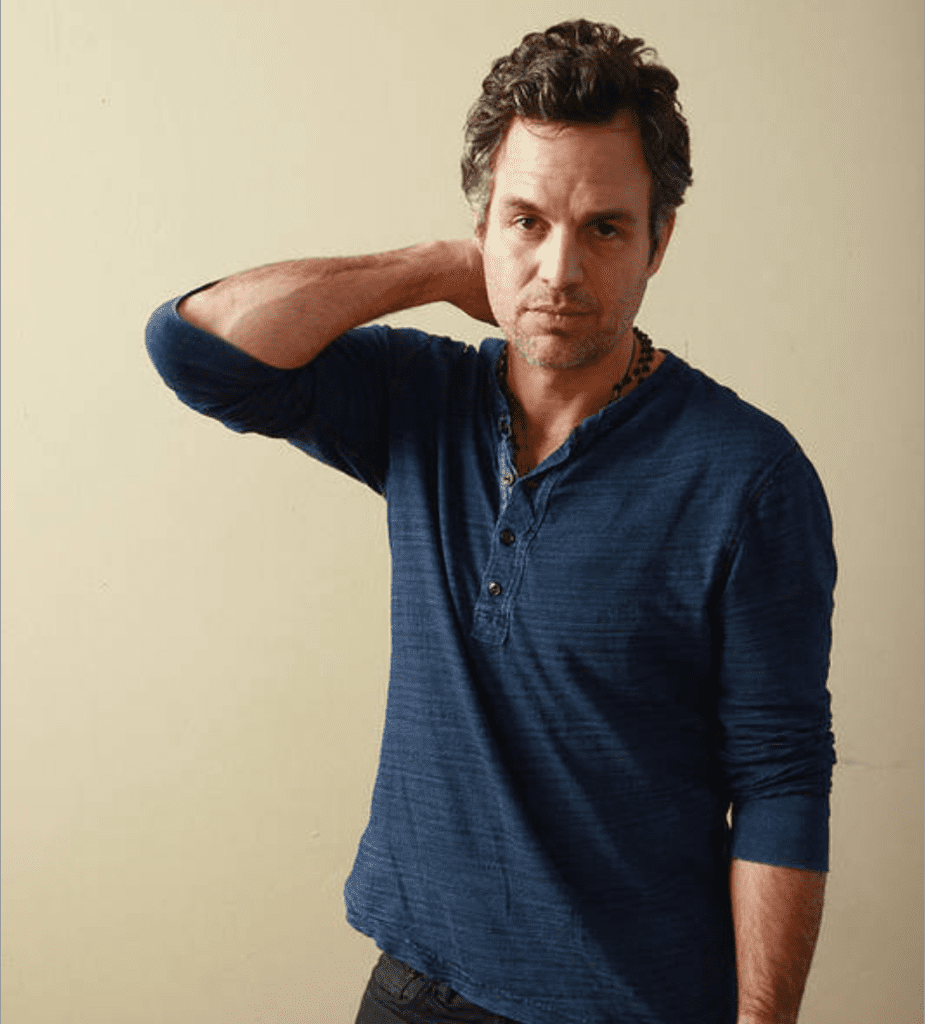

If you mention Mark Ruffalo’s name to anyone, the response is always, “He seems like a really nice guy;” or “He seems so genuine and not full of himself;” or “I love his acting;” or “I really love that guy.” And so it goes. Those responses are consistent and we’re pleased to tell you that yes, he is all those things. Yes, he is quite accessible, and yes, he’s quite unassuming, and yes, he’s a really nice guy. As far as his outstanding performances, given his multiple award nominations, that speaks volumes.

One of Ruffalo’s most compelling work was his performance in Infinitely Polar Bear, it’s one of the most powerful roles he’s played to date.

Infinitely Polar Bear

How did you go about preparing for this role? How did you find the right tone for the character?

RUFFALO: I hope it’s the right tone. The most important thing and I’ve grown up with people who are bipolar, and I’ve known people who are bipolar, and the one thing: bipolar isn’t a person. The one thing that I felt was the most important thing was to capture who Cam was, essentially. And then lay the bipolar onto that, because what bipolar is really, it’s just the extremes of emotions, and a certain sliding scale of where those emotions go, right? Things just get way out on both sides, right? A lot of that was written into the script, so Maya did a great job of helping me with that.

Who is Cam? He was just kind of curious, childlike, poetical guy who I think had a great appetite for life. And was very whimsical. The other thing is he was a Brahmin. He was the son of this blue-blood aristocracy, really; and that, I didn’t understand. I’m blue-collar; I joke with Maya, her family came over on the Mayfair a couple of hundred years ago; my family rowed over in a rowboat SO years ago.

I didn’t understand it. I didn’t understand why the family didn’t help them. I didn’t understand all these rules and ways of speaking and do’s and don’t that don’t have any sort of rhyme or reason to them other than that was the way they did it. So that was a big part of doing it. And then the fun part was riding these extremes.

And then it’s all grounded in his deep and abiding love for his daughters, and his belief in that family. What’s so touching about him is there’s nowhere else he’d rather be than with Maggie and those girls, in a way. And his illness just prevents him from being viable as a breadwinner.

Did Mayo share more with you about her own family?

RUFFALO: Totally. I was trying to get as much as I could: pictures, recordings, letters, video, anything that I could get a hold of. But mostly it was the stories that informed me who he was to me. There are a lot of great, funny things that he did that didn’t make it into the film. And I had a piece of video-probably, maybe eight minutes long-and it was him hanging out with the girls, and then him having breakfast with his mother and father. And that became a great tool for me to get an idea of his mannerisms and the way he carried himself. That was a big, important part, for Maya, too: we worked a lot on that.

When your character was on lithium, he was one way and when he went off the lithium he was another way. How did you manifest that in your behavior?

RUFFALO: A lot of these psychotropic drugs are dulling. At that time, they were over-prescribing lithium. So when you saw him when he went to the hospital, he’s heavily dosed, and it manifests himself in just this deadening, and this slurred speech, and the shakes. They shake a lot, and they put on a lot of water weight, and so that was one manifestation of its extreme. Then, when he takes it after jumping into the Charles River, and he decided he’s going to let Maggie take the girls, it just flattens everything out.

So the ups and the downs—there is no ups and downs-in a band, an emotional band that is very shallow in its highs and lows. But that was the biggest part of the lithium stuff. Cam struggled with that his whole life, and he used the alcohol-the way he talks about it, it wasn’t a joke that he sips some beer. Alcohol, at very low levels, hits basically—it does what lithium does; it has this deadening. But what happens is if you go over that, then it starts to his the same places that mania does.

We did a screening for Psychology Today, and then we did a panel, and so we had all these specialists in bipolar, and they loved the portrayal of it; but they talked a lot about how alcohol works with people who are manic depressive, and how they use it to manage it, but also, it can cause them to go into deeper mania and disassociation later.

In the movie, you and the young actresses who play your daughters use a lot of profanity against each other. Can you share with us a bit about that experience?

RUFFALO: It’s shocking when you hear it. It’s kind of funny actually. But I think the journey that those girls make is from a kind of being helpless to being independent and, in a weird way, they’re also taking care of their father as he’s taking care of them. So mainly they grow up a little bit quicker. When you look at the byproduct of this crazy, dysfunctional family, you have Maya Forbes, who’s an incredibly accomplished writer, now director, a great mom, and a great mate.

You have China Forbes, who is the lead singer of Pink Martini. She’s an incredibly accomplished, great mom, great career. They’re strong women. I look at them and think I hope my girls turn out like them. So, yeah, maybe there are things that aren’t what we imagine to be the perfect family as far as their relationship with their father, but it worked, and maybe families work way more than we think they do.

I think this is what the movie’s about I like kids who assert themselves and have a sense of self-esteem, and are willing to say what they believe is right or wrong. I think that’s healthy for a child. That’s how I raise my kids. I don’t want them swearing at me, but I’m also not afraid of words. In my family, words are something that we shouldn’t be afraid to use.

And to be honest with you, I let them swear. I tell them, “It stays in the house; people get offended by this stuff.” If they stub a toe, they’re like, “Dammit, and I think it’s funny. We use the same words. They are much worse things that could be happening to kids than them saying bad words now and again.

Your life must be a balancing act since you have such a heavy career? What’s your biggest challenge?

RUFFALO: Just being away is just sort of the craziest negative of my great blessings. And I don’t mean to complain. Movies are being made all over the world now. They’re rarely made locally. And just spending long periods away from them has been the hardest part and most challenging part.

Do your children visit you on the set?

RUFFALO: I have three special needs children. All three of my kids are dyslexic, so they need a very specific kind of schooling. They have a hard time transitioning, and so because of that, it’s very hard to take them out of school.

It would be hard for any kid to keep pulling in and out of school, and I don’t want to disrupt their lives that way. But when I’m working, and it’s summertime, they come to visit me, so we spent last year in London, and that was fun. But most of the year they are in school. So now I’ve been trying to focus on doing work near home, and how do I not work so much that’s kind of where I’m at right now.

You are so well-loved and respected, and your work is solid. Sorry to gush.

RUFFALO: You can never hear that enough. (He laughs.) When I go home, they’re not like, ”You’re the best’ They’re like, (bored) “Yeah … “

I love acting, and I don’t see a difference between the kind of acting you do in a big movie or a small movie. Mostly, when you get into different kinds of styles it’s dictated by the genre but also the director.

Each director takes on a trip, too, that’s different if you’re willing to go with them that’s different from anything else you’ve done before. I just found it interesting that I would be in these kinds of movies because generally, they don’t use actors like me in these movies.

Scarlet and I, when we were on the tour, we’re looking at each other like, “What are we doing here?” We are two indie cockroaches, and now we’re staying in these hotels.

That’s the change the business has gone through since I started when I started, You Can Count on Me—it was very clear what an indie movie was and what a studio movie was. And since then, they’ve just come closer and closer together.

Studio movies look more like indie movies, and indie movies look more like studio movies. And the characters you used to see in indie movies you’re now seeing in studio movies. It’s all mixed-up now; I think it’s better that way, personally.

What I like about indie movies is the contained nature of the energy of them. When you do a big movie, you might shoot scene 1 on day 2, and scene 2 on day 75; and so they get a little disjointed. There’s a familial—a little movie, 23 Ways—everyone’s rushing, stumbling, is vulnerable. There’s never enough money or enough people to do what you want to do. And so everyone’s relying on each other, in a way; and everyone has to be vulnerable; and there’s a very clear beginning, middle, and end that everyone’s working towards. And so that experience is generally a little bit more rough and holy. But as far as acting goes, hopefully, you’re doing the same thing with both of them.

You’re on your bike there and your skivvies—what was the temperature like?

RUFFALO: It was cold, man. It was freezing. That was real acting; it was really cold. There was a scene that was in the movie before that, where he leaves the house in one outfit, and then he comes back in that. And he’s trying to figure out where the hell, and what escapades he might have been on to come back that way. That’s a true story. That was an inciting moment. That was a crystalline moment that happened in that family-but he came back completely sunburnt in his little tighties. Yeah, that was cold.

Was there someone right offset waiting with a warm coat?

RUFFALO: When I went out, there was nobody, cause it was a wide shot. But as soon as I came running in, when I didn’t need the coat anymore, cause I’d been riding on my bike, then they were there immediately.

What do you hope the audience will take away from this film?

RUFFALO: That family happens, and that it takes all kinds. There’s a lot of room for all different kinds of families. I love the theme of family in the work. And I think that it creates space for people with mental illness that didn’t maybe films don’t generally give them. Allows this dialogue; it allows them to be people, instead of an illness. And that love is the answer, I think.

What have you fixed? Can you fix things?

RUFFALO: Totally. I tore apart my motorcycles and put them back together. Most of it just came from being poor and not being able to afford to take your car to get an oil change or change a muffler. Just the things you had to do to survive, especially early living here in California—you can’t do anything here without a car or a motorcycle, or some form of transportation. So out of necessity, I had to do a lot of stuff.

I can change the dutch plates on a 1978 Honda 250. I don’t know if I can do anything past 1980. But I’ve also done construction, house painting, and gardening work. I’ve done a lot of odd jobs, so that’s how I learned how to do that stuff.

Has that informed your work?

RUFFALO: It has. Those are the parts I’ve gotten to do and I know how to do. So there is that. But her and I, we had a nice, easy she’s got a great sense of humor, she’s game, she’s not afraid, she’s playful. And what she has that’s so perfect for that character is indomitable positivity. That’s really what Maggie had, which is Peggy, who’s Maya’s mother, who we got to work with quite a bit. And that’s what Maggie had; and I think that’s what buoyed them through all the difficult, horrible times.

She was telling me yesterday about having three crazy people up for the weekend; Cam was in a full-blown episode. And two other people were also on the spectrum of one thing or another. And she’s s normal. And she’s like, “Oh, Mark, that was such a crazy weekend, and I was just trying to keep it all together.” And I can see her bouncing around through there. She understands race, and she’s not afraid to be strong when she has to be. She’s just a great actress who’s just beginning to come into herself. She’s great; I love her.

With your huge body of work, and all of the wonderful characters you’ve created, has one lingered more than another?

RUFFALO: What my wife and I have fondly come to refer to as “re-entry,” which is me coming back into the family after walking around with some total stranger for more times in my life than not. She’s like, “You change, every character. You come and start walking like them and you behave like them, and it’s a pain in the ass sometimes. You even talk like them.”

I don’t see it personally. My feeling is you can’t come into contact with these different people without having them change you in some way. Anything we do when we come into contact with somebody, it’s personal and it’s deeply … you’re doing such intense investigation into somebody. None that I can think of have held on longer than another. They just get—they’re all in there somewhere, a little bit mixed-up in there, which can make you crazy. I’m not going to lie to you. Ten takes therapy to work your way around. I feel like it enriches my life.

One great thing about being an actor is you get invited into people’s worlds in a way that I don’t know many other people do. So, for example, doing a movie about South Boston. If I try to join a bar in South Boston, they would beat the hell out of me. They would never let me in.

But when you’re an actor and you tell them you’re playing a part of a South Boston guy, suddenly they all want to tell you and show you what South Boston is like, in a personal way. I find that to be almost across the board.

You get to see the world in a way that a lot of people don’t get to see you. And what you come to realize we’re not that different when you get rid of the accent and the cultural things; and people aren’t stuck with who they are. We are making this up a little bit as we’re going along.

And we can be pretty much whoever we want to be, and the limitations that are out there are only designed by us. That’s the one thing that I’ve come to see because there’s so much available to all of us now in a way that there’s never been.

And going from character to character, even from the point of going from Cam Stewart, taking two weeks off in bed, sick as a dog, and starting The Normal Heart. Having two weeks between those two characters that are so vastly different from one another, without much prep time at all, says to me how facile we are actually as people. Not just beliefs, but even physical life, and the way we sound, and all these things, so that’s been an interesting journey for me.

Are you planning to go back to directing?

RUFFALO: I am going to go back to directing, I’ve just been on a run of acting. Directing just takes so much time, and right now I want to spend more time with my family, so the acting has been good, though it hasn’t turned out that way.

You studied with Stella Adler, which gave you your basis, which is why you’re so wonderful. Do you always work internally with the character first? Or do you do on external life first?

RUFFALO: I work both. Sometimes it’s out; sometimes it’s in. Sometimes it’ll be, oddly enough, an exterior thing-Stella used to say, “A character is what they do and how they do it.” And so you have someone who’s [makes gesture]. That kind of person says a lot to the inside, just by doing that. And so you can get a lot of inside from the outside, and vice versa. So whatever works; whatever school of acting, they’re all trying to do the same thing: not be crappy, be interesting, and not be boring. And so I work both ways, yeah.