You’ve probably never heard of him — Why?

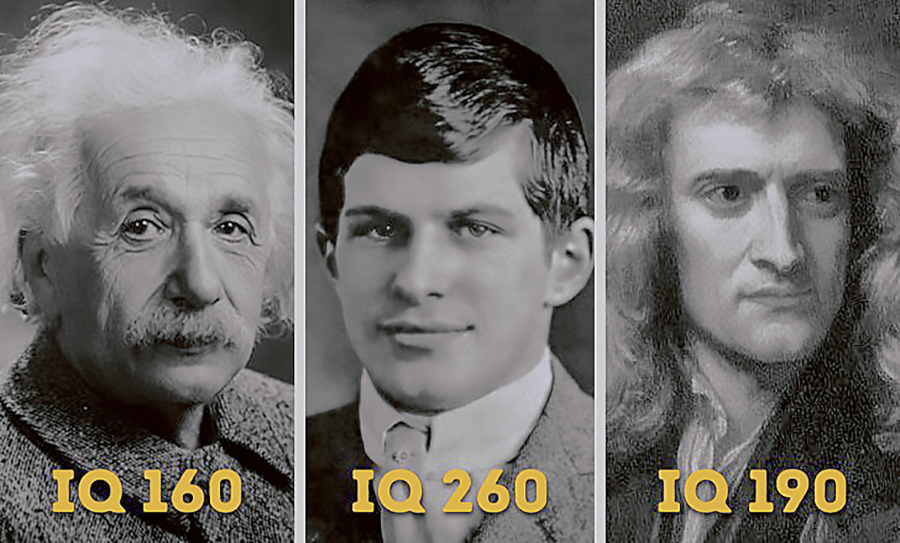

Einstein’s IQ was 160, Isaac Newton’s was 190. The man we’re talking about had an IQ of 260! His name is William James Sidis.

A Child Prodigy

Born in Boston in 1898, William James Sidis made the headlines in the early 20th century as a child prodigy with an amazing intellect.

He could read the New York Times before he was 2. At age 6, his language repertoire included English, Latin, French, German, Russian, Hebrew, Turkish and Armenian. At age 11, he entered Harvard University as one of the youngest students in the school’s history.

But as an adult, he purposefully faded into the shadows, avoiding the public scrutiny that followed him through his early years.

Sidis’ biographer Amy Wallace tells Weekends on All Things Considered host Guy Raz that he despised media attention. “He became a household name, and he hated it,” she says.

Nurturing The Early Years

Sidis’ parents were pretty smart, too. His father, Boris, was a famous psychologist, and his mother, Sarah, was a doctor.

Wallace describes them as pushy and aggressive. “They believed that you could make a genius,” Wallace says. His mother spent the family’s savings on books, maps and other learning tools to encourage their precocious son.

“One thing that was very unusual about [Sidis] compared to other child prodigies [is that] very few prodigies have multiple abilities,” Wallace says. As a young boy, Sidis invented his own language and wrote French poetry, a novel and a constitution for a utopia.

Harvard At 11 Years Old

Sidis was accepted to Harvard at age 9, but the school wanted him to wait until he was 11. Five years later, he graduated cum laude.

His Harvard days, however, were not full of happy memories.

“He had been made a laughing stock at Harvard,” Wallace says. “He admitted he had never kissed a girl. He was teased and chased, and it was just humiliating. And all he wanted was to be away from academia [and] be a regular working man.”

A Writer In Hiding

After a brief stint as a mathematics professor after graduation, Sidis went into hiding from public scrutiny, moving from city to city, job to job, often using an alias.

All the while, he wrote a number of books, including a 1,200-page history of the United States and a book on streetcar transfer tickets, which he loved to collect. His books were never widely published, and he used at least eight pseudonyms.

“We probably will never know how many books he published under false names,” Wallace says.

Recently, an inscribed copy of a book he wrote in 1925 — The Animate and the Inanimate — was sold in London to an anonymous collector for 5,000 pounds — almost $8,000.

Exposed By The New Yorker

Sidis lived successfully out of the limelight until 1937 when the New Yorker magazine sent a female reporter to befriend him and gather information for an article on what had happened to the boy wonder.

According to Wallace, Sidis thought the article’s description of him was humiliating and “made him sound crazy.” After the article was published, “Sidis decided to come out of the woodwork and out of hiding, and sued the New Yorker,” Wallace says.

Sidis argued in court that the magazine had libeled him, and he won. Shortly afterward, in 1944, he died from a brain hemorrhage at age 46.

Despite his unhappy childhood and the media scrutiny he endured as a child prodigy, Wallace thinks Sidis led a happier life as an adult.

“People who knew him adored him,” Wallace says. “So I think he really went from being completely traumatized as a young boy to becoming a happy man.”