This monument is a tribute to the spirit of humanity and to a man who persevered against the odds to build something that will endure for many generations to come.

On a partial of land in the mountains, a family was supposed to live quietly ever after. That was the Bishops’ plan. It was here in 1966 where Jim asked Phoebe to be his girl, a week after they’d met in Pueblo and shared a Coke. He was 21, in very good shape from weightlifting. She was 17, uninterested in boys before meeting him. They were both quiet. “We just meshed,” Phoebe Bishop says. “We were soul mates.” They married in a matter of months.

On this secluded land in the mountains, Bishop began building a home, a stone cottage. Then someone stopped on Colorado 165 and asked if he was building a castle because the stone and arching design looked that way. More stopped with the same question. No, he’d tell them. He was building a home. More kept coming because they heard a castle was being built.

“The people want a castle,” he told his wife one night around a campfire at the property, where they’d been living in a tin shack while the cottage was under construction. “I think I need to build a castle.”

So the cottage would be a castle. The high school dropout would do something amazing, something his alcoholic father never could do. And he would do it for poor families like the one he grew up in, for those needing something to enjoy for free. He ignored people who told him he could profit from the idea. To this day, the cost of tourist attractions angers him.

The castle man

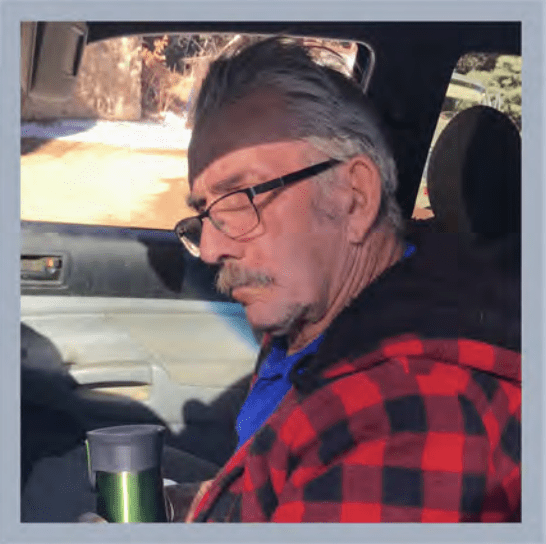

Bishop takes pills for his anxiety in the mornings and evenings. But during the day, when he’s around his castle visitors, he relents.

Bishop takes pills for his anxiety in the mornings and evenings. But during the day, when he’s around his castle visitors, he relents.

“In the afternoon, he’s fit to be tied and he’s hard to be around,” Phoebe Bishop, his wife since 1967, says at their home in Pueblo.

In the afternoon, he’s the crazy castle man. “It’s part of the appeal,” says Daniel Bishop, 43, the eldest of three children. “It’s something that has taken over. … He thrives on the attention.

“It would do him good to be a part of something,” the son adds, “to have an outlet for his energy that wasn’t what he’s always been doing. Like a self-help group. But then, I don’t know. He’d just be seen as Jim Bishop, the castle builder.”

This is a story about an ordinary man who did something extraordinary and gave up a lot to do it, including himself. Obsessions change people. Jim Bishop the castle builder is not the Jim Bishop who once was.

His wife hears about his rants, and when he comes home at night, she tries to tell him he doesn’t have to be like that. “He says, ‘That’s how I am,'” she says. “He says, ‘I’d rather be that than the zombie people knew for two years.'”

He looked dead at times in 2014. He was prescribed meds that August, after a nervous breakdown landed him in a psychiatric ward for 11 nights. Months later, he was diagnosed with cancer. He couldn’t escape bed some days. Other days, he’d call Jorgenson for a ride to the castle. Bishop needed to work.

Those close to him have seen the castle become the man’s life source, but Jorgenson notices the harmful effects of what it brings every day.

The Internal Revenue Service

In the castle’s early years, he became dismayed by bureaucracy: The Internal Revenue Service telling him his land couldn’t simply be tax-exempt because he felt he was doing something good for people; the Bureau of Land Management told him he couldn’t simply take rocks from a national forest; Custer County telling him his plans were not according to code; the Department of Transportation told him he couldn’t post signs on the highway.

“The highway signs were a big push for him going fanatical,” Daniel Bishop says. “He saw signs for ski resorts, the big-business, big-money places, and he couldn’t understand why there couldn’t be signs for people who couldn’t afford to ski.”

Jim Bishop pressed on, ignoring bureaucracy, essentially becoming an outlaw. He eventually put out donation cans that remain around the castle.

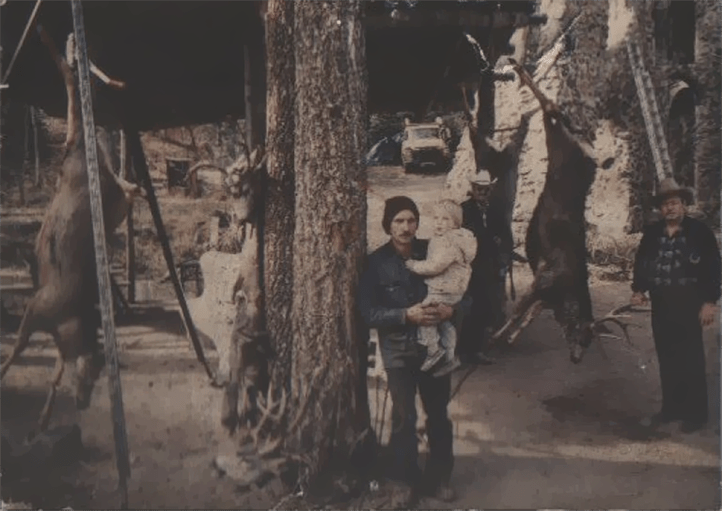

Daniel Bishop was asked what life would be like if the castle never happened. “Maybe there would’ve been more money growing up. Maybe it would be like it was when he was young, just the two of them in the woods, hunting peacefully.”

Surely, Daniel Bishop would not have carried this pain, this guilt that came after helping his father with parking spaces at the castle one afternoon, that came after he cut down a tree, and saw his brother Roy die.

“I don’t like to think about should’ve, could’ve, would’ve,” the son says.

Doing it for Roy

For a moment at the castle, Jim Bishop is alone, putting together a jungle gym for kids. Gone are the people snickering behind their phones.

Around those people, he was asked why he keeps working on the castle. And now, as he is alone, the question does not elicit a rant.

“My ego,” he says, softly and simply.

There’s something else. He chokes up trying to explain.

He talks about Roy, his little boy who died nearby, where there is now space for parking.

“It was the day after Mother’s Day,” he says, sobbing, his voice rising. “I’ll tell you what, we’ve been through years of s— up here, and people say, ‘How can you stay here?’ Well, what am I gonna run to?! Roy loved this place. He loved this place.”

Bishop wipes at his dirty face with his dirty hands. “Dammit,” he says, turning back to the jungle gym. “I gotta get to work.”

Alert for parents

RoadsideAmerica.com, an online guide to attractions and oddities, has a page for Bishop Castle that includes an alert for parents: “(It) may look like Hogwarts, but Jim Bishop is no cuddly Dumbledore. He’s a tough-talking man with strong beliefs, and sometimes he expresses them bluntly and loudly.” And indeed, on this recent afternoon, a mother shuffled her children away as Bishop went on.

Find more about Jim Bishop and his Castle on Facebook

Bishop Castle Website