Don’t fuck it up with pompous bullshit

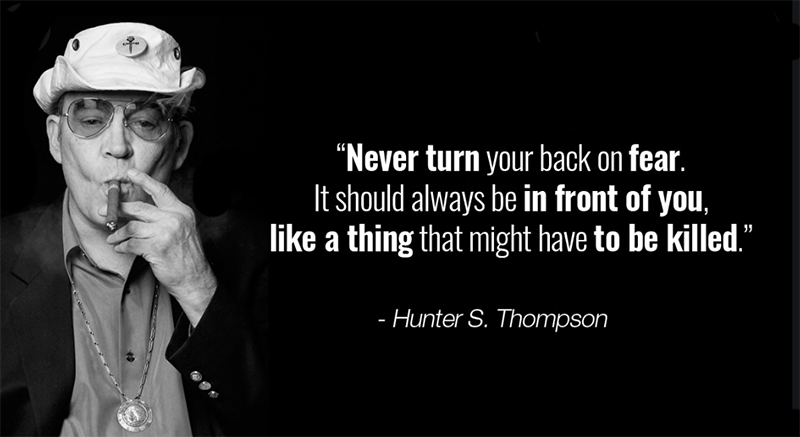

In January 1970, Hunter S. Thompson wrote Jann S. Wenner a letter praising Rolling Stone‘s definitive coverage of the disastrous Altamont festival. “[Print’s] a hell of a good medium by any standard, from Hemingway to the Airplane,” Thompson wrote. “Don’t fuck it up with pompous bullshit; the demise of RS would leave a nasty hole.” A bond was formed, and over the next 30 years, Thompson would do much to redefine journalism in the pages of the magazine. He lived and wrote on the edge in a style that would come to be called Gonzo journalism. That term captured his lifestyle, but it didn’t really do justice to Thompson’s command of language, his fearless reporting or his fearsome intellect.

Thompson was born in Louisville, Kentucky, served in the Air Force, and worked as a journalist in Puerto Rico before moving to San Francisco, where an article about the Hells Angels turned into a book project. He spent almost two years riding with the outlaw motorcycle gang, and in 1966 he published a bestseller that took readers deep inside a subculture largely inaccessible to the outside world.

Kindred Spirits

Thompson and Rolling Stone were kindred spirits. After he wrote to the magazine, Wenner invited him to the office to discuss a piece that would be called “The Battle of Aspen,” about Thompson’s effort to bring “freak power” to the Rockies. Thompson had tried to get Joe Edwards, a 29-year-old pot-smoking lawyer, elected mayor; Thompson himself was running for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado. “He stood six-three,” Wenner remembered years later, “shaved bald, dark glasses, smoking, carrying two six-packs of beer; he sat down, slowly unpacked a leather satchel full of travel necessities onto my desk – mainly hardware, flashlights, a siren, boxes of cigarettes, flares – and didn’t leave for three hours. By the end, I was suddenly deep into his campaign.” Thompson and Edwards lost their bids by slim margins, but Thompson’s fate as a self-described “political junkie” was sealed.

A year later, Thompson sent Rolling Stone the first section of a new piece he was working on. “We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold,” it began. “I remember saying something like, ‘I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive…’ And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about 100 miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas.”

A defining literary experience

“Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” became Thompson’s defining piece, and a defining literary experience for generations of readers. It had begun as an assignment from Sports Illustrated when Thompson was asked to go to Las Vegas to write a 250-word photo caption on a motorcycle race, the Mint 400.

Introducing himself as a “doctor of journalism,” he chronicled the fuel he brought along: “two bags of grass, 75 pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multicolored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers . . . and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls… Not that we needed all that for the trip, but once you get locked into a serious drug collection, the tendency is to push it as far as you can.”

The heart of the American dream

The trip became less about covering the race and more of, in Thompson’s words, “a savage journey into the heart of the American dream.” When he submitted 2,500 words to Sports Illustrated, the piece was rejected, along with his expenses. But when Wenner read it, he seized on it. “We were flat knocked out,” recalls then-managing editor Paul Scanlon. “Between fits of laughter, we ran our favorite lines back and forth to one another: ‘One toke? You poor fool. Wait until you see those goddamned bats!’”

Rolling Stone sent Thompson back to Vegas to expand the piece, reporting on the National District Attorneys Association’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. The results were hilarious and electrifying. “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” ran in two parts, in the issues of November 11th and 25th, 1971, with illustrations by Ralph Steadman, and was published in book form the next year. (In 1998, it became a film starring Johnny Depp.)

Pack journalism

Thompson was also reshaping what it meant to write about politics. He filed 14 dispatches for Rolling Stone from the 1972 presidential campaign trail. He lacerated the “waterheads,” “swine” and “fatcats” of D.C. culture – a tone far different from the reverent approach of the time – and lifted the curtain on the mechanics of press coverage. He exposed “pack journalism,” puff pieces born out of schmoozing sessions between journalists and campaign aides. Many of Thompson’s observations ring true today: “It’s come to the point where you almost can’t run [for president] unless you can cause people to salivate and whip on each other with big sticks,” he wrote. “You almost have to be a rock star to get the kind of fever you need to survive in American politics.”

But getting work out of Thompson was becoming difficult. The magazine put him up at hotels in San Francisco or Florida, and stocked his room with booze, grapefruit and speed. A primitive fax machine, which Thompson called his “Mojo Wire,” was installed in the Rolling Stone offices, and he’d transmit his copy a few pages at a time at odd hours, adding the transitions and endings later. He would often call Wenner at 2 a.m. to discuss the pieces. “It was a bit like being a cornerman for Ali,” said Wenner. “Editing Hunter required stamina, but I was young, and this was once in a lifetime.”

In correspondence between Thompson and Wenner, Thompson demanded albums and speed; Wenner chastised him for blowing deadlines, keeping the staff late and even stealing cassettes from his house. (“I did a lot of rotten things out there but I didn’t steal your fucking cassettes,” Thompson wrote.)

Epic Vietnam piece

Thompson had become a celebrity – and it slowed him down. He was immortalized as Uncle Duke in Doonesbury. “All that kind of trapped him, between the fame and the drugs,” said Wenner. “After the election and Watergate, he wrote small things for us. But he’d miss flights and never turn anything in.” In one memo from around that time, Wenner checked in on seven features, none of which ever came to fruition. In 1975, Thompson traveled to a failing Saigon for a planned epic Vietnam piece, but he spent most of his time there drinking in the hotel courtyard with other correspondents. He conducted several interviews with Jimmy Carter that the former president remembered as lengthy and revealing, but Thompson lost the tapes.

Thompson had become a celebrity – and it slowed him down. He was immortalized as Uncle Duke in Doonesbury. “All that kind of trapped him, between the fame and the drugs,” said Wenner. “After the election and Watergate, he wrote small things for us. But he’d miss flights and never turn anything in.” In one memo from around that time, Wenner checked in on seven features, none of which ever came to fruition.

In 1975, Thompson traveled to a failing Saigon for a planned epic Vietnam piece, but he spent most of his time there drinking in the hotel courtyard with other correspondents. He conducted several interviews with Jimmy Carter that the former president remembered as lengthy and revealing, but Thompson lost the tapes.

1982 Pulitzer divorce trial

Still, there were flashes of brilliance, such as his coverage of the 1982 Pulitzer divorce trial in Palm Beach, Florida, which summed up the Eighties culture of greed as it was still taking form. In 1992, he published “Fear and Loathing in Elko,” a surreal fiction piece in which he met future Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, stranded on a road with two prostitutes. “It was a remarkable comeback,” said Wenner, who saw “Elko” as a bookend to the 1971 classic. “ ’Vegas’ is so fun and hopeful. ‘Elko’ is this bitter, very dark tale, kind of a descent into some of the worst impulses of the human spirit.”

My time has come to die, Dougie

Thompson wrote one final piece for Rolling Stone, in 2004. In an uncharacteristically humble tone, he made a plea to readers to vote. By that point, Thompson’s back pain had become chronic, and he required a wheelchair. His book editor Douglas Brinkley recalled taking a trip with Thompson to New Orleans in January 2005, where he was humiliated when he couldn’t climb the stairs at a party thrown by James Carville. “He sulked at the downstairs bar, muttering cryptic things like, ‘My time has come to die, Dougie,’ ” Brinkley remembered.

A month later, Brinkley reported that Thompson got into a shouting match with his wife, Anita Thompson, after he nearly shot her with a pellet gun. They made up the next day, but when she phoned Thompson from a nearby health club, she heard strange clicking noises. After she hung up, he put a .45-caliber gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Suicide Note

Thompson left a suicide note, titled “Football Season Is Over,” which was printed in Rolling Stone. “67,” Thompson wrote. “That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.” Thompson’s death recalled the suicide of his literary hero Ernest Hemingway. “Hunter had really gone from being a celebrity to being a legend,” Wenner said. “Part of that legend is his suicide, much like Hemingway.”

My central memory of that time is that everything we were doing seemed to work. . . . Buy the ticket, take the ride. Like an amusement park. … Thanx for the rush.

One final wish

Thompson had one final wish. In August 2005, more than 200 friends, including Wenner, Jack Nicholson, John Kerry and Johnny Depp, gathered at Thompson’s Colorado home, where his ashes were shot out of a 153-foot cannon under a full moon. In March 2005, Thompson appeared on the cover of the magazine, with remembrances from Depp, George McGovern and Thompson’s son, Juan, among others. Included was a letter Thompson wrote to Wenner in 1998, recalling his early days at Rolling Stone:

“My central memory of that time is that everything we were doing seemed to work. . . . Buy the ticket, take the ride. Like an amusement park. … Thanx for the rush.”